The do’s and don’ts of making sauerkraut

Sauerkraut seems simple. Just stick some cabbage and salt in a jar. Let it sit.

Wa-lah.

But, if you’re not careful, you’ll end up with pink kraut, spoiled sauerkraut, or even something that could make you sick.

So, while sauerkraut appears straightforward, there are a couple steps that are key to ensuring a successful batch. To help out, here’s a quick guide to make sure the magic of sauerkraut works for you.

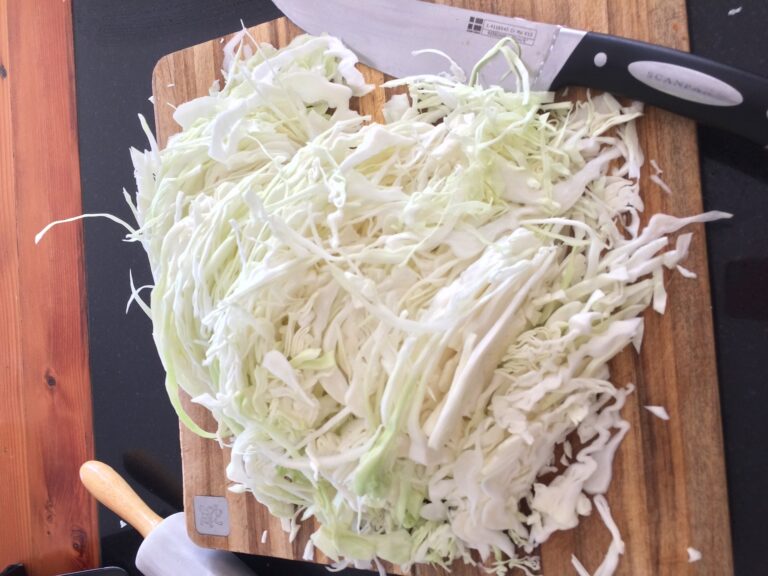

Step 1- Shredding

It’s always nice to start with a gimme.

Take your heads of cabbage and remove a couple of the outer leaves or any parts that look defective. Wash to remove any dirt or debris. Next, and this is the important part, shred the cabbage into smaller pieces to expose a higher amount of surface area.

You’ll see in the next step that increasing the amount of surface will help the salt do its job.

Step 2- Salting

Without adding 2-3% salt to the cabbage, you’d never end up with sauerkraut.

And it’s not just added to make the dish taste better. In this case, its purpose is two-fold and neither is associated with flavor.

First, the addition of salt to the shredded cabbage results in an osmotic imbalance. In other words, there’s lots of water inside the leaves, but very little outside where the salt is. This forces the water and nutrients inside the shredded cabbage to leach out to strike a balance. In doing so, all the nutrients are now available to any microorganisms that are naturally living on the cabbage.

Given that cabbage is about 90% water, this results in an energy rich fluid that also dissolves all the salt. The fluid contains everything from sugars to vitamins and minerals. It’s the perfect energy drink for any microorganisms around.

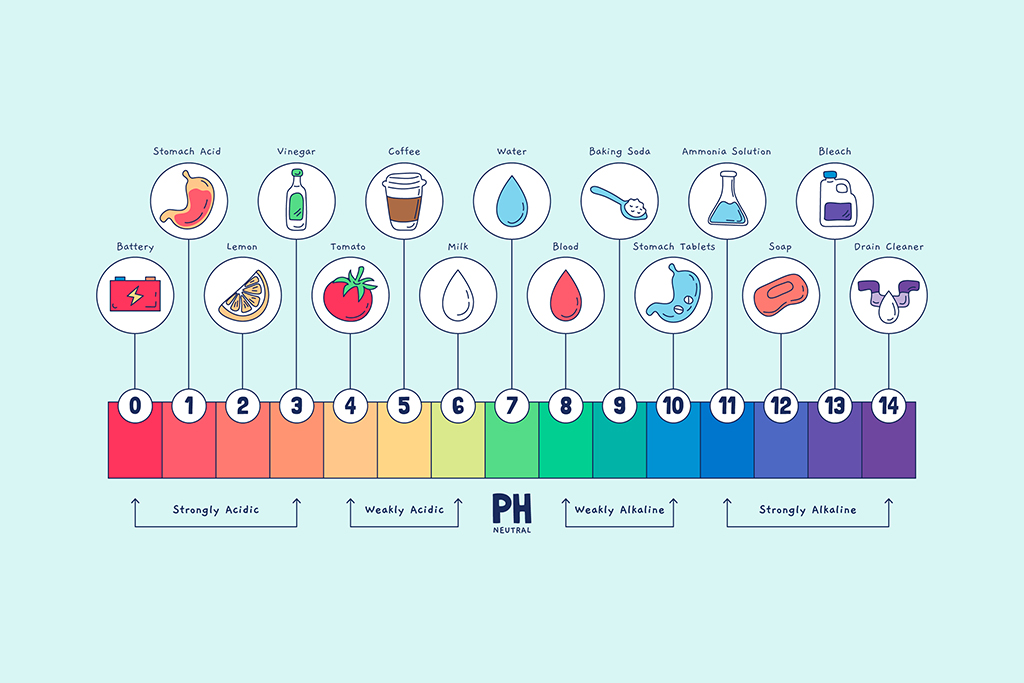

Second, salt helps control which microorganisms will be able to grow. Just like humans, microorganisms have preferences about the environment they live in. And it turns out, many don’t like the salty conditions provided by the sauerkraut. The presence of salt actually inhibits the growth of many pathogenic, or bad microorganisms, which can make us sick.

One last note on salt— make sure it’s evenly distributed. You don’t want any areas where the cabbage leaves have more or less salt. These regions will lead to undesirable microorganisms growing and even spoiling the product.

Step 3- Packing & Sealing

I know this step seems pretty intuitive, but the sealing part is particularly important.

Traditionally, sauerkraut was packed into a tierce or crock, but any container that can tightly seal should work. Choose a vessel that once packed with the cabbage and salt mixture will be safely sealed off from the air, or more specifically oxygen.

This will help generate anaerobic, or oxygen free, conditions within the container. A necessary step for part of the fermentation later on.

If oxygen is to be able to sneak into the sauerkraut during storage, undesirable microorganisms will be able to grow, typically yeast and molds. This usually results in a spoiled product.

Step 4- Fermentation

Sauerkraut fermentation is known as a wild fermentation, since we’re using the microorganisms naturally found on the cabbage leaves. This is different from the fermentation done in beer production where specific cultures are added.

From the outside, the five or so weeks of fermentation makes it appear like nothing is happening, but inside the microorganisms are hard at work. In fact, sauerkraut fermentation is fairly complex and is a bit like a relay race; the microorganisms that start the fermentation are not the ones that finish it. They pass it onto another species.

Each type of microorganism important for sauerkraut fermentation can be classified as a lactic acid bacteria. This means they eat simple sugars from the cabbage, like glucose and fructose, to produce lactic acid. The population of lactic acid bacteria naturally found on cabbage leaves is only a small percentage of the total amount of microorganisms; however, the conditions provided during fermentation are perfect for them to thrive.

The first bacteria to get to work are typically Leuconostoc mesenteroides. These bacteria generate carbon dioxide, which makes the environment fully anaerobic if the container is sealed properly. They also make plenty of lactic acid, acetic acid, and other important flavor compounds.

Unfortunately for Leuconostoc mesenteroides, as they produce more acid, conditions become too acidic for them to live. Fortunately for us, the acidic environment inhibits most types of spoilage microorganisms and any enzymes from deteriorating the cabbage.

As the population of Leuconostoc mesenteroides declines, Lactobacillus brevis begins to take over the fermentation. Lactobacillus brevis continues to produce more lactic acid until they also produce such acidic conditions that their numbers begin to drop.

At this point, the acid-tolerant Lactobacillus plantarum will finish the fermentation. The fermentation is done when all the sugars in the cabbage have been consumed. This usually takes about five weeks. Once complete, so much acid has been generated that the cabbage will be preserved for months.

Sauerkraut Defects

As someone who used to do quite a bit of homebrewing, I know how exciting it can be to break into a new batch after fermentation has been completed. But as I’ve occasionally experienced with beer, the fermentation for sauerkraut can also go awry. Here are a couple common mistakes to be aware of.

First, if the texture seems off, perhaps oddly soft, something has gone wrong with your fermentation. It likely took place at too warm of temperatures, the vessel wasn’t completely sealed, or not enough salt was added. Be careful as undesirable bacteria may have been able to grow.

If your sauerkraut has a pink color to it, the yeast naturally present on the cabbage took over the fermentation. Yeast like Torula glutinus are known for growing on the surface of cabbage and make their presence known with the unique pink coloring acquired after fermentation. Toss it.

If you’ve opened your sauerkraut for the first time and it just seems rotten, you again lost control of the fermentation. Likely a mix of bacteria, yeast, and molds were thriving instead of the specific lactic acid bacteria we wanted. Again, make sure the vessel was completely sealed off to the air and no oxygen was able to sneak in.

To many, sauerkraut simply looks like some food shoved in a jar, but from a microscopic perspective, those cabbage leaves are bursting with activity and full of life.

It takes a complex succession of microorganisms to convert our salty cabbage leaves into a food that can be preserved for months or even years. But, without just the right bacteria taking their turn to ferment, things can go really sour. And quickly.

Because as I hope you’ve learned, while making sauerkraut seems simple enough, there’s actually a lot of science behind its success.