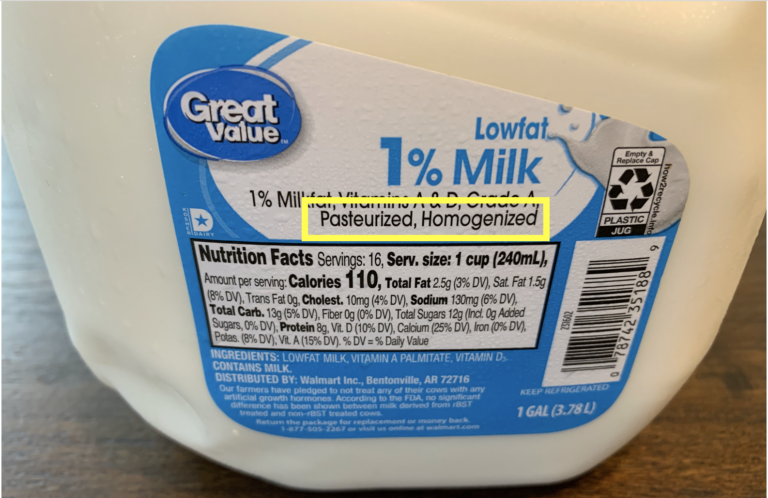

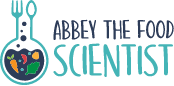

Two words we take for granted

In 1938, one food was responsible for 25% of all the foodborne illness in the US.

Care to venture a guess to which?

If you’re not sure, let me give you another clue.

This food caused a bunch of nasty diseases like tuberculosis, brucellosis, salmonellosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, septic sore throat, and dysentery.

What’s your best guess now?

I’m betting good ole’ milk didn’t come to mind, but it used to be deadly (and raw milk still is). It’s really scientific breakthroughs in processing milk — like homogenization and pasteurization — that have made it the safe, wholesome product we enjoy today.

So, what do those two words mean anyways?

Pasteurization makes milk safe

Named after the French Scientist Louis Pasteur, pasteurization is a heat treatment meant to destroy microorganisms in our food.

In the 1860s, Pasteur realized that he could delay the spoilage of beer and wine by heating the liquid (sounds to me like Pasteur was a scientist of the people and was doing the experiments that really mattered).

Pasteur was thrilled to discover a step that could elongate the shelf life of food and beverages. At the time, he didn’t link it to the destruction of microorganisms since no one knew these tiny organisms existed yet. It would be a couple years before that connection was made.

Fast forward to today and in the U.S. there’s two main types of pasteurization: low temperature long time (LTLT) holds milk at 63°C (145°F) for 30 minutes whereas high temperature short time (HTST) pasteurization can be done in only 15 seconds at 72°C (161°F).

Now, these times and temperatures aren’t simply random. They were specifically chosen since the conditions destroy the most heat resistant pathogen (disease-causing microorganism) C. burnettii. So, if we know pasteurization has destroyed C. burnetti, we can confidently say it has also killed any other pathogens since they are more sensitive to the heat.

Although pasteurization destroys disease-causing microorganisms, it still leaves plenty of spoilage organisms as well as any toxins or spores. This explains why our milk does eventually spoil.

If you want to kill all life forms present in milk you need to bring out the maximum heat—ultra high temperature processing.

What’s ultra high temperature (UHT) milk?

To make UHT milk there’s no messing around. This milk is held at 150°C (300°F) for 2–3 seconds which destroys all life (microorganisms and spores).

This process obliterates both disease-causing and spoilage microorganisms.

The only problem is, using such high temperatures changes the milk a bit. It has a slightly brown color to it, and you’ll notice a cooked flavor that pasteurized milk doesn’t have.

On the bright side, microorganisms are so unlikely to grow after UHT processing that the milk can be stored at room temperature for over a year. No refrigeration needed, which makes it quite convenient.

Homogenization keeps milk stable

Imagine you twist open a milk carton to find a layer of fat sitting on top of the remaining liquid.

Would you drink this milk?

Gulp down that fatty layer before hitting the watery liquid that’s left?

Most of us would probably say no. We’re used to milk being one homogenous liquid even if it’s composed of both fat and water.

This uniform composition lends milk its characteristic texture and requires that the tiny oil droplets stay evenly dispersed within the greater liquid phase. No separation.

For that, we have the process of homogenization to thank.

During homogenization, high pressures are used to force hot milk through a tiny orifice, which breaks the oil into microscopic-sized droplets.

Usually, milk goes through two steps of homogenization. The first step reduces the size of the oil droplets, but often results in large clusters of droplets, so a second pass through another orifice is used to separate these clumps into individual oil droplets.

As the oil droplets become smaller, they are much slower to float to the top.

So slow that we don’t notice any changes as a carton of milk sits in our refrigerator for a week or two. That’s the magic of homogenization.

When it comes to the milk we buy in the grocery store, pasteurization is used to destroy any microorganisms that could make us sick and homogenization produces tiny oil droplets that are uniformly dispersed. Both processes help make the milk we enjoy today.

And I will say, it’s pretty nice to not have to worry about tuberculosis or scarlet fever when eating your morning cereal. Sounds like a pretty rough way to start the day.

One Response

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d without a doubt donate to this superb blog!

I suppose for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS

feed to my Google account. I look forward to brand new updates and will

share this website with my Facebook group. Chat soon!