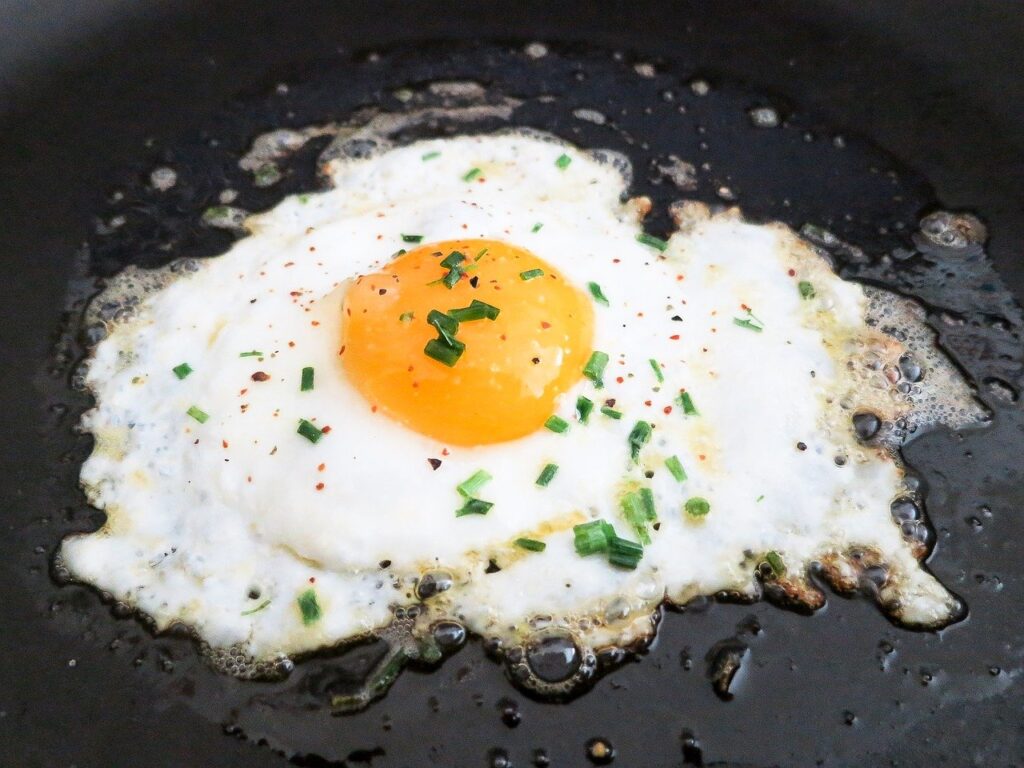

Using science to avoid that chewy, rubbery texture

We’ve all done it.

Been rushed or too impatient to fry an egg properly. Cranked up the heat, only to be completely disappointed with the result

Because what do we end up with?

An egg that feels like plastic in our mouth. It’s rough and tough. Not the light and fluffy breakfast we were dreaming of.

Never again! Because once you understand how an egg cooks, you’ll never repeat that amateur mistake.

First, what’s really happening when you fry an egg?

When you first crack an egg into the frying pan it’s liquid-like and runny. By adding heat, the egg becomes more solid and elastic. On a microscopic level, the heat from the pan is changing how the proteins in the egg whites and yolk are behaving.

Although the proteins in the egg whites are different from the egg yolk, each can be represented as a necklace. Just like a necklace is made up of many beads to create a long strand, proteins are made up of many amino acids to create long molecules.

Initially, each protein strand is all balled up and curled in upon itself. These are called globular proteins.

This is like tossing your necklace onto your dresser haphazardly — it becomes all entangled and knotted.

That’s the initial state of each protein. It’s just interacting and folded upon itself.

But when heat is added this entirely changes the game.

The energy added to the egg makes the proteins unravel and open up. This is called denaturation. The proteins lose their native structure and become long, unfolded strands wiggling around. As more and more proteins unravel, they start to become intermingled with each other and form networks.

This is like all your necklaces becoming a giant knot in your jewellery box. It becomes hard to separate one necklace from another.

When proteins form these vast, entangled networks within the eggs, it sets up a gel. A gel simply means the protein matrix is so strong, it surrounds and immobilizes other molecules like water or fat.

And when we fry our eggs, we are purposefully denaturing proteins and forming a gel.

So what we normally think of “cooking” an egg really involves certain microscopic transformations.

Now, how do we control these proteins to make soft, airy eggs?

It all comes down to a balance of time and temperature.

The proteins in the egg white are more sensitive to heat than those in the egg yolk.

The egg whites will begin to denature starting at 140°F and would be entirely denatured once a temperature of 149°F is reached. Once these proteins begin to be denatured, the egg whites lose their transparency and ability to flow.

The proteins in the yolk act a little different. They won’t even start denaturing until a temperature of 149°F is reached. Remember that’s the upper temperature for egg whites. The egg yolk will reach full denaturation at 158°F.

But denaturation and aggregation don’t occur instantaneously. It takes time for the proteins to unravel and make contacts with one another to form the gel matrix. This is why low heat settings are recommended for frying eggs. You can’t rush them.

Instead, cooking the eggs at a slow rate or low temperature setting is best. This allows time for denaturation and coagulation to occur while still remaining at the lower end of the temperature range. The gel matrix formed by the proteins will give a soft and tender egg.

Where people tend to go wrong is using high temperatures to fry an egg, which causes two alterations to the gel formed by the proteins.

With such high heat, much of the water evaporates, which allows the protein matrix to shrink and become more dense.

The egg is essentially being cooked too fast.

The second problem is that the proteins don’t have enough time to unravel and aggregate before extremely high temperatures are reached.

Since the egg is rapidly heating up, it quickly goes above the temperature necessary to denature some of the proteins. Shooting way above the needed temperature means all the proteins will be forced to unravel. This results in more protein strands available to interact with each other resulting in a strong, super compact gel matrix.

This tightly knit gel is what gives a badly fried egg with a tough and firm texture.

Fried eggs aren’t the type of breakfast you can rush. You need to keep it low and slow to yield that soft, airy texture.

If you don’t, those pesky proteins will get the best of you. Nothing like a piece of rubber for breakfast.