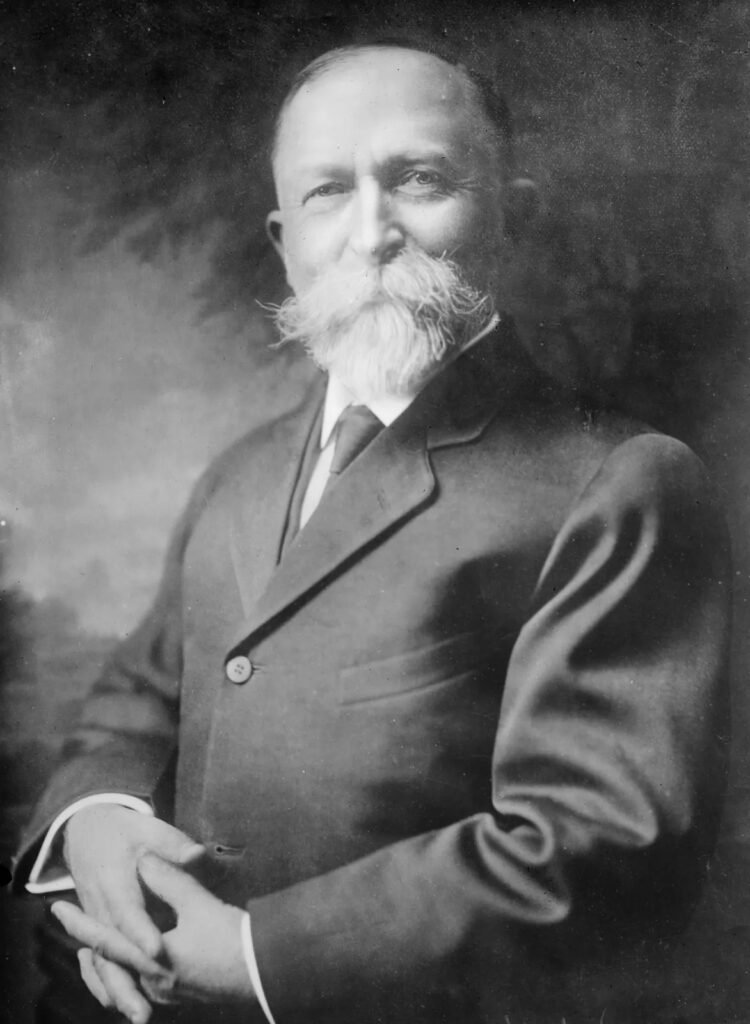

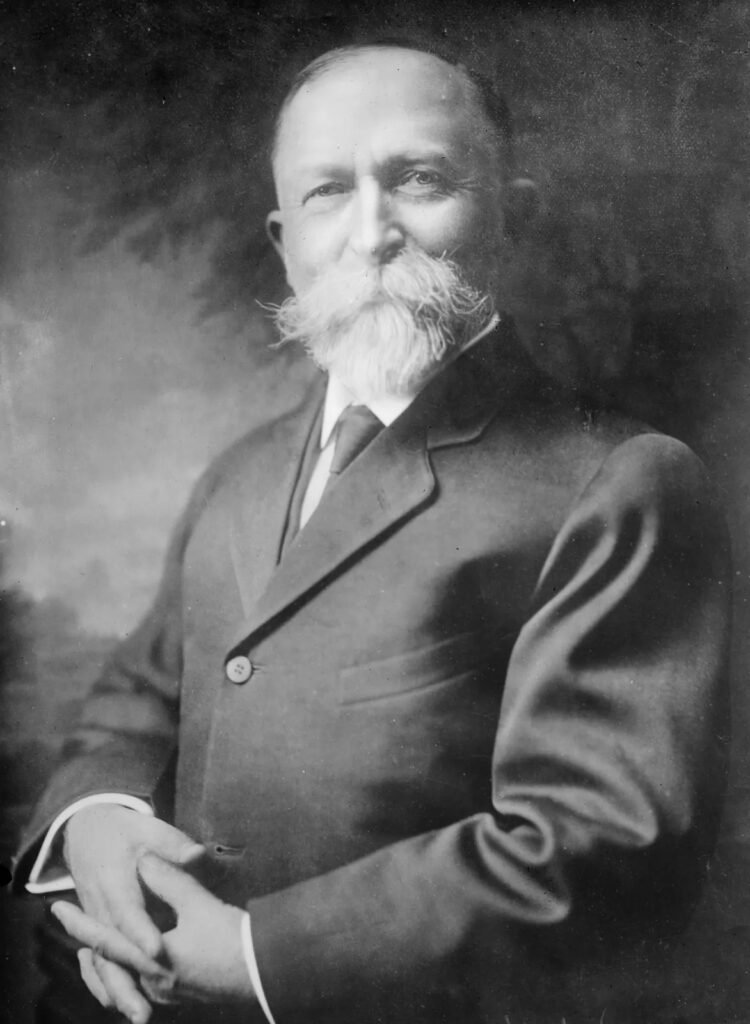

Fueled by his religious beliefs, J.H. Kellogg invented an entirely new food segment.

If you’ve eaten breakfast cereal, you know the name Kellogg. It has long been associated with the first meal of the day, and the popularization of breakfast cereals can largely be credited to the Kellogg family.

While the entire aisles of the grocery store are solely dedicated to breakfast cereals today, there was a time when none of these products existed. That was until an eccentric man named John Harvey Kellogg became dedicated to inventing his own “pure” food products. Due to his religious beliefs that flavorful foods were sinful and unclean, Kellogg was forced to think creatively and innovate when preparing meals.

While J.H. Kellogg was peculiar by many standards, he was a well-educated man for his time. Not only was he a medically trained doctor, but also a scholar, author, and inventor. Like many historical figures, to understand Kellogg’s success and discoveries, we must first uncover what influenced him as a young man.

The early years of J.H. Kellogg

Kellogg was born into a humble family in Tyrone, Michigan, in 1852. He was just one of the 16 children in the Kellogg clan, which soon moved to Battle Creek, Michigan. If Battle Creek rings a bell, it’s because it’s known as the “Cereal City” — both C.W. Post and Kellogg had roots in the region.

The Kellogg family was heavily involved in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. This Christian offshoot stressed the importance of healthful living and maintaining your body. Seventh-day Adventists also believed that the holy spirit was housed in the human body, so defiling the body was akin to sullying the holy spirit.

During Kellogg’s youth, two church leaders, James and Ellen White, started promoting even stricter health reforms. Said to have visions from God, the Whites began propagating a list of banned foods like tobacco, coffee, tea, and medicines. Soon, unhealthy lifestyles were considered immoral. It was preached that if you didn’t maintain your personal health and tarnished your body with banned foods, your chance of ascension into heaven was greatly reduced.

Kellogg strongly adhered to the strict religious teachings first disseminated by the Whites. He was a firm believer that food could corrupt the human body and mind. Religious teachings also blamed food for triggering immoral activities and thoughts. At times, Kellogg’s ideas about unclean foods seem downright preposterous. For example, here is a snippet from one of his health booklets that was circulated to the public:

The use of highly seasoned food, rich sauces, spices and condiments, sweetmeats, and, in fact, all kinds of stimulating foods has an undoubted influence upon the sexual nature of boys, stimulating those organs into too early activity and occasioning temptations to sin which otherwise would not occur. Young people should carefully avoid mustard, pepper, pepper sauce, spices, rich gravies, and other similar kinds of food.

They are not wholesome for either old or young, but for the young, they are absolutely dangerous.

Although some of Kellogg’s ideas seem a bit absurd, he did focus on nutritious diets at a time when the influence of a healthy lifestyle was widely ignored. In fact, it was exactly these beliefs and limitations on food that spurred Kellogg to his biggest invention yet — breakfast cereal.

The founding of the Western Health Reform Institute

The Whites dedicated their lives to the church and erected the Western Health Reform Institute to carry out their stringent lifestyle beliefs. The Institute was sort of half hospital, half health resort. Patients were taught about healthy diets, suitable exercises, and good health practices.

In its early days, the Whites’ Institute was only a small cottage and two-story residence hall. Over the years, it rapidly expanded to cover an entire campus of buildings capable of holding hundreds of residents.

The Western Health Reform Institute ran successfully for years under the Whites’ care; however, as the medical field advanced, their patients began demanding more science-backed medicine.

It was a time when the general public was embracing science. Unfortunately, the Whites had just lost their last medically trained physician.

This was no doubt bad timing for the Whites, but the search for a new doctor began. The two decided it was best to hunt for a new medically educated doctor who was also a Seventh-day Adventist. They understood that it would be easier for someone who was raised in the church to embrace the culture and practices at the Institute. Plus, this individual would never challenge the Whites on their religion.

To find the perfect match, the Whites searched their congregation. They had previously met the Kellogg family during a fundraising campaign for the Western Health Reform Institute. In fact, the Kellogg’s had donated money to help build it.

To the Whites, John Harvey Kellogg seemed like the perfect fit. He was active, young, bright, and raised during the health reform movement. Perhaps most importantly, they believed he was capable of taking only the “good” from medical training, while resisting any kind of temptations that questioned his religion.

Kellogg’s medical school education

A deal was struck between the Whites and J.H. Kellogg: The Whites would pay for his medical schooling as long as he promised to return to Western Health Reform Institute to practice.

Kellogg spent his first year of medical school at the University of Michigan Medical School and then moved to New York City. He completed his degree at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1875.

While Kellogg had been in New York, the Institute had expanded into eight buildings on 15 acres of land. The Whites were ecstatic at the prospect of Kellogg’s return, but the young doctor felt he could not lead the entire facility.

Due to his hesitation, Kellogg worked out a compromise with the Whites and accepted only a temporary position at the Institute. Ironically, only a year later, Kellogg accepted the role of medical director, which he held until his death.

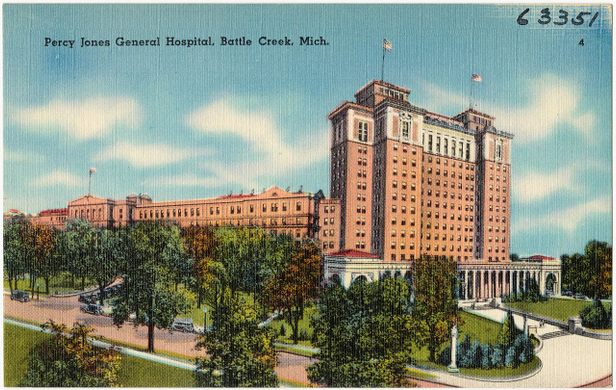

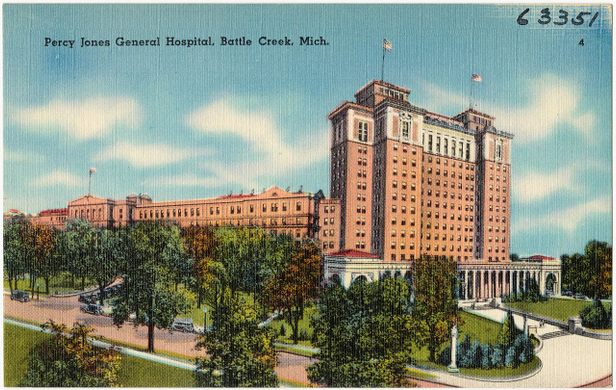

The Battle Creek Sanitarium

As the medical director, Kellogg decided the Western Health Reform Institute needed a new name. Playing on the words sanitary and sanatorium, the facility was renamed Battle Creek Sanitarium and affectionately shorted to “the San.”

Kellogg was crucial in pulling the sanitarium out of its mostly hydrotherapy-based practices into a more scientific approach incorporating medical principles.

Although he was a medical doctor, he often wavered between his medical education and religious beliefs. He was said to wear white from head to toe for “health reasons.” What those health reasons were, I couldn’t find. However, he was a talented surgeon who performed 165 surgeries consecutively without a single mortality. For the time, that record was remarkable.

Over his many years as medical director, Kellogg compiled all his ideas regarding healthy living into one theory he called “biological living.” This meant living to prevent disease, not just reacting to disease once it had set in. All his patients were to follow a vegetarian diet, perform aerobic exercises, drink 10 glasses of water a day, and abstain from any caffeine or alcoholic substances.

He became obsessed with food and its effect on the human body. He soon took over the San’s cafeteria and enacted a much stricter menu. Meat was one of the first foods to be banned because Kellogg believed it slowed patient’s recovery after surgery. He also claimed meat consumption was responsible for a wide range of illnesses ranging from liver stress and tooth cavities to tuberculosis and mental illness.

The strict diet also aligned with Kellogg’s religious views and attempted to help Adventists keep their bodies pure and free from sin. To do so, any rich sauces, seasonings, and spices were removed from the cafeteria’s recipes. Meals became a combination of whole grains, vegetables, and fruit. There was no sugar, salt, or dessert allowed. Kellogg wholeheartedly believed in this regimen; just read a quote from one of his books, “Plain Facts for Old and Young: Embracing the Natural History and Hygiene of Organic Life”:

The custom of making food pungent and stimulating with condiments is the great, almost sole, cause of gluttony. It is one of the greatest hindrances to virtue. Indeed, it may be true that the devices of modern cookery are the most powerful allies of unchastity and licentiousness.

The problem was, the San soon had a reputation of serving foul-tasting food. People became discouraged from visiting, and patients left and sought help elsewhere. While some people may have seen this a setback, Kellogg was a deeply religious man and embraced it as an opportunity. He saw a need for “pure” foods and wanted to fill it. He began looking into different ingredients and how to process them into more appealing forms.

The invention of granola

Kellogg knew that by cutting meat from the San’s menu, there was a severe lack of protein in most of the meals, so he began experimenting with protein-packed nuts.

He affectionately referred to nuts as “the most pure food.” Since many patients at the San had problems chewing or with digestion, Kellogg searched for ways to process the nuts to ease these bodily functions.

Kellogg first found success by carefully grinding down nuts into a fine paste, or what might be called nut butter today. He soon began to research nut and grain combinations, formulating over 80 such products. By far, his greatest breakthrough was identifying how to process grains into a more desirable texture.

Drawing inspiration from a colleague who had created a product called Shredded Whole Wheat Bread, Kellogg investigated how to grind and roll grains. He found the process promising and quickly rigged together the first flaking machine. Wheat was the original grain run through a machine that utilized borrowed pastry rollers from Kellogg’s wife and a paper-cutting knife from an Adventist publishing house.

The flaking process was soon patented by Kellogg, which involved cooking the wheat, letting it cool, running it through the pastry rollers, and then scraping it off with the paper-cutting knife to form small pieces. The most ingenious part of this machine was that any type of grain could be processed. The number of products that could be made was limitless.

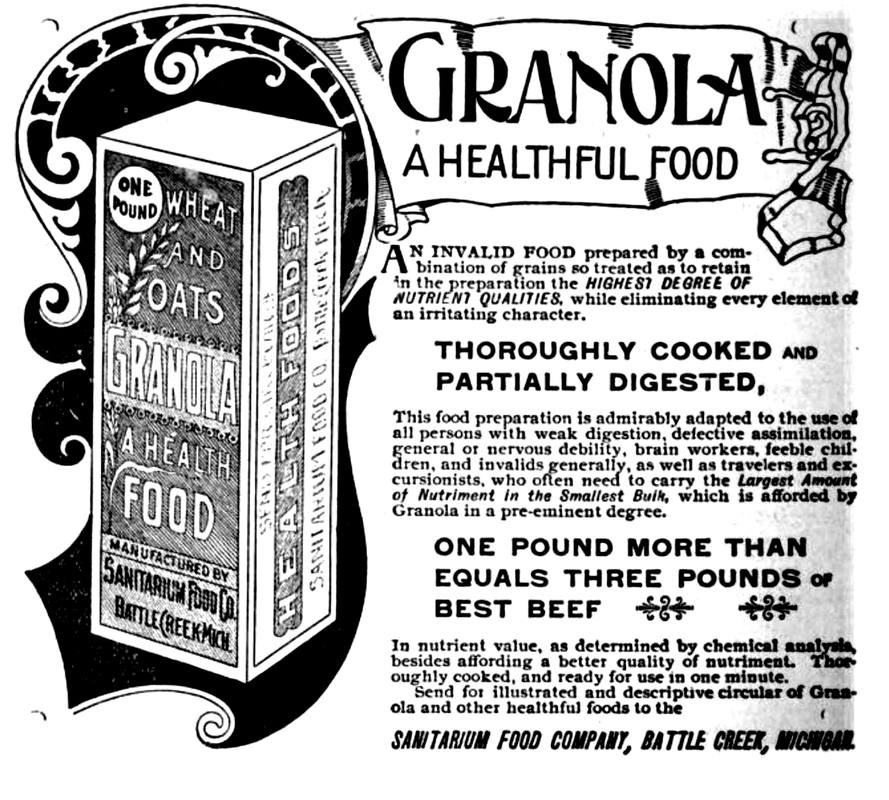

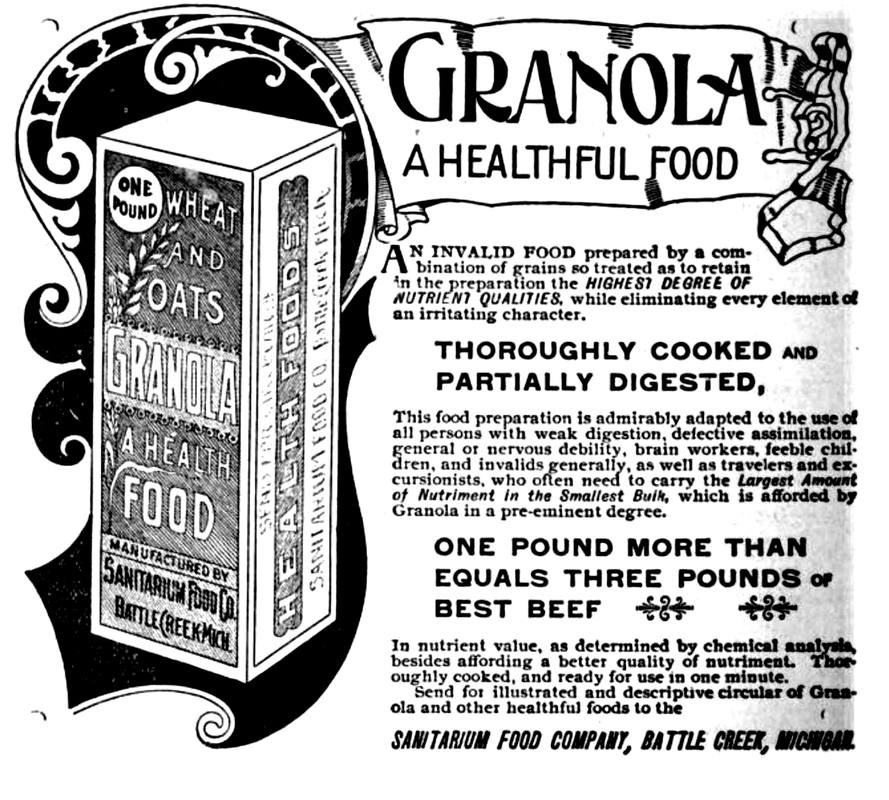

More and more of Kellogg’s time was consumed by experimenting with new food that could be served at the sanitarium. So much so, that he soon created the Sanitarium Food Company to help handle the extensive amount of food production. Under this company, his first wheat-flaked cereal, granola, was launched.

It wasn’t long before granula was switched to granola. A lawsuit was filed against Kellogg by another Seventh-day Adventist, James Caleb Jackson, who had a wheat product on the market by the same name. Although Jackson’s product wasn’t as successful as Kellogg’s, it did start the trend of adding milk to breakfast cereals. It turns out, Jackson’s cereal contained wheat nuggets so hard that they had to be soaked in water or milk overnight to be edible.

As his new food products became more successful, Kellogg aimed to make the sanitarium more focused on food manufacturing. Unfortunately, the other directors of the San didn’t support Kellogg in this business venture. They urged him to return to his work, which directly benefited the sanitarium and its patients.

The Kellogg brothers launch Corn Flakes

Kellogg found a new partner in his brother William. The two joined up and founded the Sanitas Nut Food Company. Using the same jerry-rigged machine that created granola, the brothers launched their first corn-based cereal, Sanitas Corn Flakes.

Unlike his brother, William Kellogg was extremely business-savvy. He spearheaded an expansive marketing and advertising campaign after Corn Flakes first launched, helping to make it a huge hit. The two brothers seemed to perfectly match each other’s weaknesses. John Harvey took an interest in finding new processing methods for food, while William was responsible for the business side of the company.

As well as the brothers worked together, in the end they were motivated by very different forces. William wanted to expand the company and reach a wider consumer base, while John Harvey was only interested in creating pure and healthful food that followed his strict religious protocol.

This fundamental difference in beliefs resulted in the brothers’ eventual split. In an attempt to reach more consumers, William wanted to add sugar to the rather dull cornflakes. Of course, John Harvey was vehemently against this idea, opposing it for both religious and health implications.

It was a quarrel the brothers couldn’t resolve, and John Harvey left his post at Sanitas Nut Food Company to focus more on his work at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. This meant that Will had full control of the brothers’ cereal company. As you may have guessed, William added sugar to the cereals, making them popular with the average family. To this day, the signature you see on Kellogg’s cereal boxes is William K. Kellogg.

The Legacy of J.H. Kellogg

There is no doubt that without the creative ventures of John Harvey, the Kellogg Cereal Company would not currently exist today. He invented the flaking process and many of the first products, although Will first promoted these cereals into mainstream society. Today, the Kellogg Company owns many popular brands like Rice Krispies, Frosted Flakes, and Special K.

John Harvey’s passion always remained with the sanitarium, and he was a success on his own terms. Under his careful guidance, the San grew into a successful business that was a mixture of spa, clinic, and resort. The grounds expanded to include lecture halls, baths, a gymnasium, private suites, research labs, and a conservatory.

Sources

- Balmer, B. (1991). John Harvey Kellogg and the Seventh-day Adventist Health Movement, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Bauch, N., & Curry, Michael. (2010). A Geography of Digestion: Biotechnology and the Kellogg Cereal Enterprise, 1890–1900, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Kellogg, J. (1888). Plain facts for old and young: Embracing the natural history and hygiene of organic life (rev. ed.).F. Segner.

- Davis, Ivan. (2004). Biologic living and rhetorical pathology: The case of John Harvey Kellogg and Fred Newton Scott. Michigan Academician, 36(3), 247.

- Jackson, Dudrick, & Sumpio. (2004). John Harvey Kellogg; surgeon, inventor, nutritionist (1852–1943). Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 199(5), 817–821.

- Kreiser, Christine M. (2011). Breakfast cereal. (The First). American History, 46(4), 15–15.